Knowledge base completion

This blog post is mirrored on on eClub’s blog.

My name is Michal and I came to eClub Prague to work on an awesome master’s thesis. I am interested in AI and ML applications and I sought the mentorship of Petr Baudiš aka Pasky. The project we settled on for me is researching knowledge base completion.

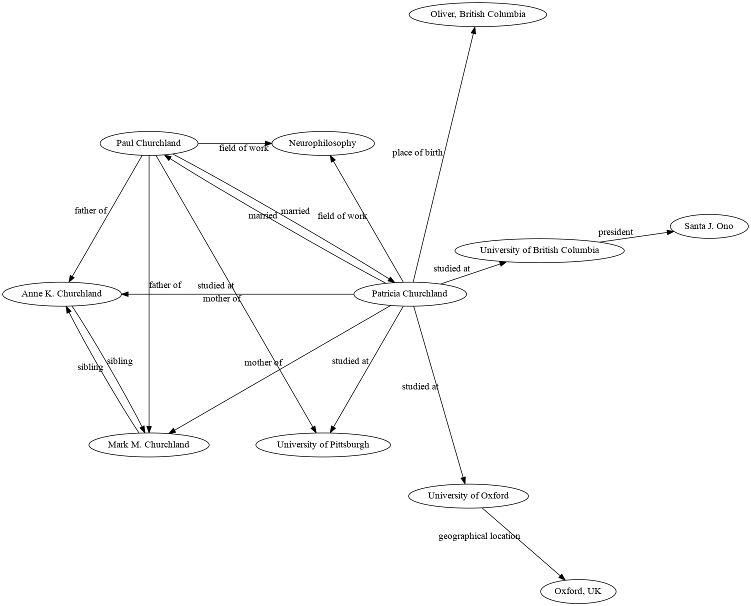

You may already know something about knowledge bases. Knowledge bases, also known as

knowledge graphs, are basically knowledge represented as graphs: vertices are

entities (e.g., Patricia Churchland, neurophilosophy,

University of Oxford) and edges are relations between

entities (e.g., Patricia Churchland studied at University of

Oxford).

Patricia Churchland in a hypothetical

knowledge base

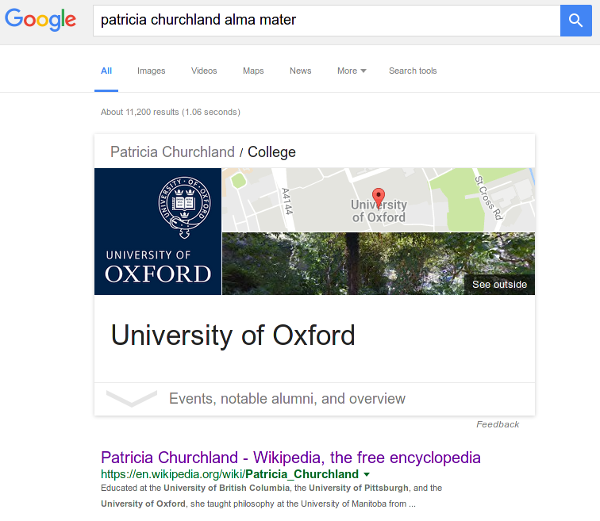

Knowledge graphs are useful[citation needed]. The most famous knowledge graph is Google’s eponymous Knowledge Graph. It’s used whenever you ask Google a question like “Which school did Patricia Churchland go to?”, or maybe “patricia churchland alma mater” – the question is parsed into a query on the graph: “Find a node named Patricia Churchland, find all edges going from that node labeled studied at, and print the labels of nodes they point at.” Look:

Google’s Knowledge Graph is based on Freebase (wiki), which is now frozen, but its data is still publicly available. Other knowledge bases include DBpedia, which is created by automatically parsing Wikipedia articles, and Wikidata, which is maintained by an army of volunteers with too much free time on their hands.

Because knowledge graphs are useful, we would like them to contain all true facts about the world, but the world is big[citation needed]. And since we want to represent everything in knowledge graphs, we’d need a really big number of editors. Real-life knowledge graphs miss a lot of facts. Persons might not have their nationalities assigned, cities might be missing their population numbers, and so on.

Someone had the bright idea that maybe we could replace some of the editing work by AI, and indeed, so we can! When we try to add missing true facts into a partially populated knowledge base, we are doing knowledge base completion.

Researchers have thrown many wildly different ideas at the problem, and some of them stuck. For example:

- Extracting relations from unstructured text. This means I take a knowledge

base, some piece of text (I’m using Wikipedia articles), and I try to

fill the gaps using the text.

The canonical approach is to train a classifier for each relation type, for example the relation actor played in movie. The classifier takes a sentence as its input, and outputs a number between 0 and 1, which represents the classifier’s estimate on the likelihood this sentence represents the relation. So, on sentences likeUniversity of Oxford is in Oxford, UK.orMarie Curie died of radium poisoning., we’d like to see low scores. On the other hand, sentences likeArnold Schwarzenegger played in the movie Terminator.should score close to 1.

A problem with this approach is that we’d need a really large training set to train our classifier well, and who has the time to label 10k+ sentences those days? Fortunately, we can use a neat trick called distant supervision. Interested? Read about it in this paper. - Mining for graph patterns. In real life, we know that if Peter is the

father of John and Kate is John’s mother, it’s pretty likely that Peter and

Kate might be married. So, if our knowledge base contains the facts

Peter is the father of JohnandKate is the mother of John, then if the knowledge base doesn’t say thatPeter is married to Kate, we could expect that to be an error of omission. On the other hand, if we add the fact thatPeter is married to Marie, that counts as evidence against Peter being married to Kate.

There are algorithms that look for such patterns (and more complex ones) in the incomplete knowledge graph and then use these patterns on the same graph to assign likelihoods to missing relations. One is called PRA (Path Ranking Algorithm), another one SFE (Subgraph Feature Extraction). Matt Gardner has an implementation of both. - Embeddings. This means that we invent a space with, say, 50 dimensions,

and somehow represent entities and relations within that space. We choose

this representation so that the embedding then informs us about which

relations might be true, but missing in the knowledge graph.

For example, say we represent people as points in a 2D plane, and we represent theis mother ofrelation as a step to the right and up, and theis father ofrelation as a step to the right and down. Of course, you can’t really represent all the complexity of family relationships this way, but if you tried to get as close as you could, you’d end up with a figure where two people who are siblings would probably end up close together. Behold: embedding according tois mother ofandis father ofjust told us something about whois sibling ofwho!

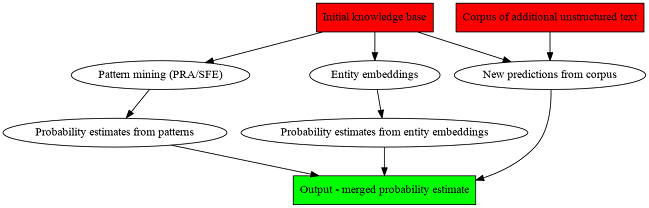

In my thesis, I plan to replicate the architecture of Google’s Knowledge Vault (paper, wiki).

Google created Knowledge Vault, because they wanted to build a knowledge graph even bigger than The Knowledge Graph.

The construction of Knowledge Vault takes Knowledge Graph as its input, and uses three different algorithms to infer probabilities for new relations. One of these algorithms extracts new relations from webpages. The second one uses PRA to predict new edges from graph patterns. The third one learns an embedding of Knowledge Graph and predicts new relations from this embedding.

Each of these different approaches yields its own probability estimates for new facts. The final step is training a new classifier that takes these estimates and merges them into one unified probability estimate.

Finally, you take all the predicted relations and their probability estimates,

you store them, and you have your own Knowledge Vault. Unlike the input

knowledge graph, this output is probabilistic: for each Subject,

Relation, Object triple, we also store the estimated

probability of that triple being true. The output is much larger than the input

graph, because it needs to store many edges that weren’t in the original

knowledge graph.

Why is this useful? Because the indiviual algorithms (extraction from text, graph pattern mining and embeddings) have complementary strengths and weaknesses, so combining them gets you a system that can predict more facts.

My system is open-source and extends Wikidata. The repository is at https://github.com/MichalPokorny/master.

So far, I have been setting up my infrastructure. A week back, I finally got the first version of my pipeline, with the stupidest algorithm and the smallest data I could use, running and predicting end-to-end!

The system generated 116 predictions with an estimated probability higher than 0.5. Samples include:

| Subject | Relation | Object | Probability | Is this fact true? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northumberland | occupation | Film director | 0.5913 | False |

| mathematician | occupation | Film director | 0.6201 | False |

| Jacob Zuma | member of political party | Zulu people | 0.5159 | False |

| Mehmed VI | country of citizenship | Ottoman Empire | 0.5479 | True |

| Brian Baker | country of citizenship | Australia | 0.5523 | False |

| swimming | occupation | Film director | 0.6229 | False |

| West Virginia | member of political party | Tennessee | 0.5107 | False |

| Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani | country of citizenship | Princely Family of Liechtenstein | 0.5289 | False |

| Sheldon Whitehouse | member of political party | Washington, D.C. | 0.5086 | False |

| Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam | country of citizenship | United States | 0.5349 | False |

| Italian Communist Party | country of citizenship | United States | 0.5545 | False |

| Henri Matisse | country of citizenship | French | 0.5004 | False |

| Lawrence Ferlinghetti | country of citizenship | United States | 0.5471 | True |

| Michael Andersson | occupation | Film director | 0.6283 | False |

| Brian Baker | country of citizenship | Canada | 0.5187 | False |

| John E. Sweeney | member of political party | Republican Party | 0.5036 | True |

Okay sooo… not super impressive, but pretty good for a first shot. At least it does a bit better than rolling a bunch of dice :)

It’s basically a logistic regression over a bag of words. The dataset are 10 000 Wikipedia articles about persons. My task now is to use smarter algorithms to get better results, adding other algorithms (graph patterns and embeddings), running over a larger dataset and fleshing out the architecture.

I’d enjoy talking at length about the various design choices and cool tools I’m using, but I was told 1 A4 page would be quite enough, so I’ll cut my proselytization short just about now.

Let’s get back to work. Have a fine day, and may your values be optimally satisfied!